If I Wear a Large Shirt What Dress Size

Inside the fight to take back the fitting room, led by designers like Melissa McCarthy, startups like Le Tote and shoppers like you

Inside the fight to take back the fitting room

By Eliana Dockterman

I have always hated fitting rooms. It's not just that I hate the mirrors meant to trick me into thinking I'm skinnier or the curtains that never close all the way so strangers can glimpse me trying to squirm into too-tight jeans. What I really hate is why I have to go to fitting rooms in the first place: to see if I've distilled my unique body shape down to one magic number, knowing full well that I probably won't be right, and it definitely won't be magic. I hate that I'm embarrassed to ask a salesperson for help, as if it's somehow my fault that I'm not short or tall or curvy or skinny enough to match an industry standard. I hate that it feels like nothing fits.

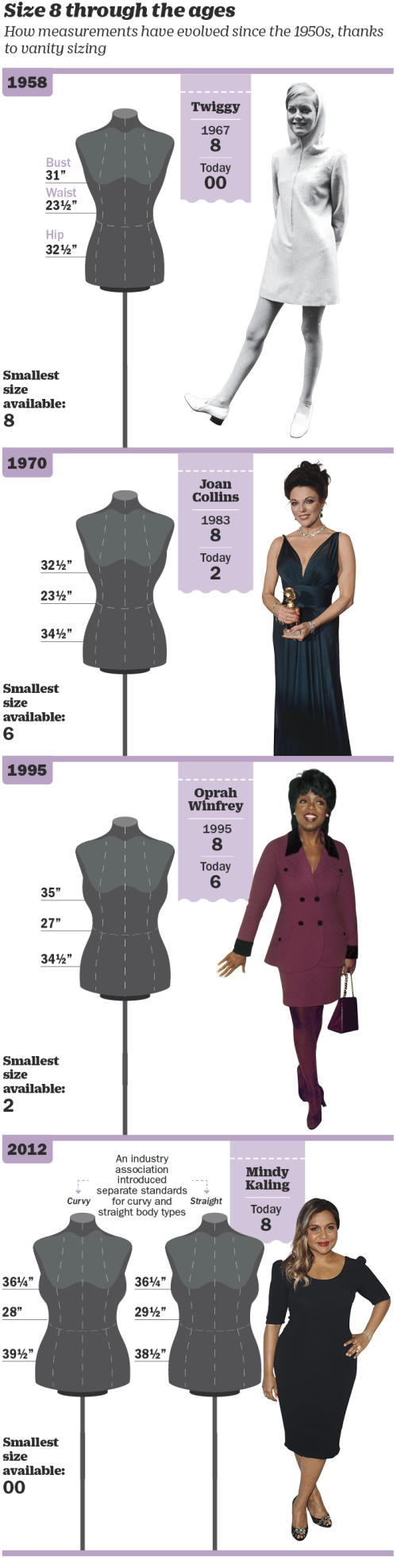

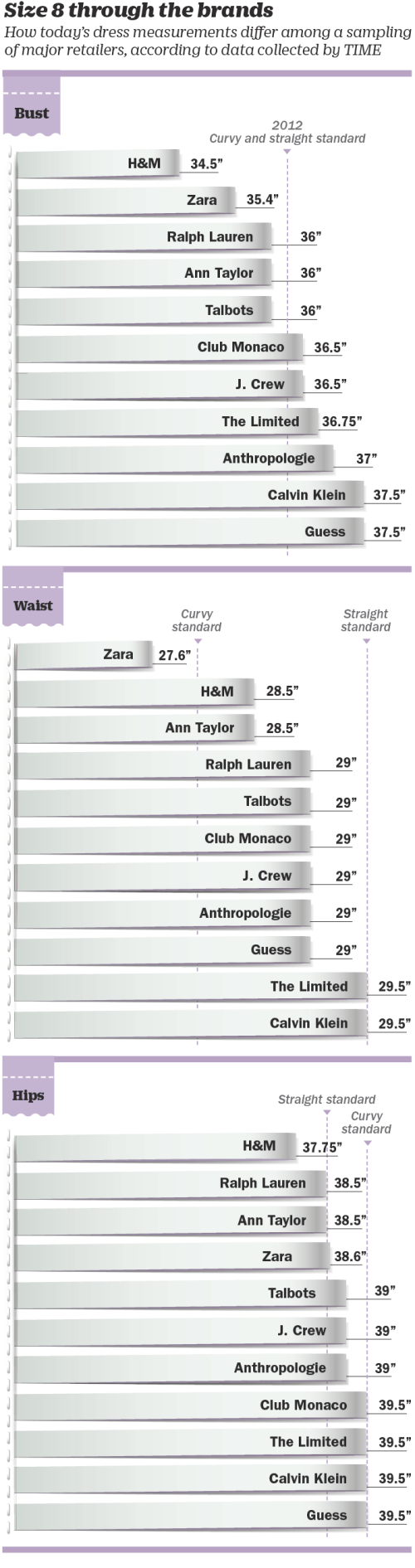

And I'm not alone. "What's your size?" has always been a loaded question, but it has become virtually impossible to answer in recent years. The rise of so-called vanity sizing has rendered most labels meaningless. As Americans have grown physically larger, brands have shifted their metrics to make shoppers feel skinnier—so much so that a women's size 12 in 1958 is now a size 6. Those numbers are even more confusing given that a pair of size-6 jeans can vary in the waistband by as much as 6 in., according to one estimate. They're also discriminatory: 67% of American women wear a size 14 or above, and most stores don't carry those numbers, however arbitrary they may be.

"Insanity sizing," as some have dubbed this trend, is frustrating enough for shoppers who try on clothes in stores. But now that $240 billion worth of apparel is purchased online each year, it has become a source of epic wastefulness. Customers return an estimated 40% of what they buy online, mostly because of sizing issues. That's a hassle for shoppers and a costly nightmare for retailers, who now spend billions covering "free" returns.

Clearly, modern fashion has a fit problem. And while it does affect men, whose shirts and jeans rarely bear honest measurements, it's a much more sweeping issue for women—not just because we have more clothing options but also because we are more closely scrutinized for what we wear. When we get married or interview for a job or play professional sports or run for President of the United States, we encounter a whole set of standards and expectations. We can be shamed for an outfit that's too slutty, too dowdy, too pricy—take your pick. That's the burden women carry into the fitting room. And when we can't find clothes that fit, let alone clothes we like, it can be infuriating.

The debate over sizing is an emotional one, especially right now, when so many shoppers are rejecting labels of all kinds, from sexual orientation to gender to, yes, size. For decades, major retailers have generally catered to one (white, slim) consumer even as America has gotten more diverse. Now shoppers are pushing back. They're turning away from stores like Victoria's Secret that market a single way to be sexy. They're demanding that mass-market chains like Forever 21 carry a wider range of sizes in-store. Even celebrities, like Beyoncé and Melissa McCarthy, are calling out high-fashion designers for ignoring the millions of women with curvier figures.

But underlying it all is the same maddening question: At a time when consumers are more vocal than ever about what they want and need, and retailers are losing money by sticking with the status quo, and tech companies have streamlined every other part of the shopping process, why is it still so hard to find clothes that fit? And what, if anything, can be done about it?

I'm inside an office closet in San Francisco holding two different dresses, both made by the same brand, both labeled size "small." They've been handed to me by Ruth Hartman, the chief merchandising officer of Le Tote, a startup that measures clothing from major brands in order to recommend the right fit, rather than just the right size, to customers. When I try on the dresses, it's immediately clear why such a company exists: The first one is tight enough that I struggle to breathe. The second balloons around me.

Hartman nods knowingly. "It's common," she says. "I always try on four pairs of a size-8 jean in the same brand because they all fit differently." The predicament is so absurd, it sounds like a joke. (In fact, it is one on NBC's upcoming comedy The Good Place, set in a heaven-like locale where there's a boutique called Everything Fits.)

This madness is partly our own fault. Studies have shown that shoppers prefer to buy clothing labeled with small sizes because it boosts our confidence. So as the weight of the average American woman rose, from 140 lb. in 1960 to 168.5 lb. in 2014, brands adjusted their metrics to help more of us squeeze into more-desirable sizes (and get us to buy more clothes). Over time this created an arms race, and retailers went to extremes trying to one-up one another. By the late 2000s, standard sizes had become so forgiving that designers introduced new ones (0, 00) to make up the difference. This was a workable issue—albeit an annoying one—so long as women shopped in physical stores with help from clerks who knew which sizes ran big and small.

Then came the Internet. People started buying more clothes online, trying them on at home, realizing that nothing fit, and sending them back. And retailers got stuck with the bills—for two-way shipping, inspection and repair. Now vanity sizing, which was once a reliable sales gimmick, sucks up billions of dollars in profits each year.

So why don't retailers just stop doing it? In theory, many (or even most) of them could agree to one standardized set of measurements, as mattress companies do, so customers would know exactly what they're getting when they order a "size 12" dress. This tactic, known as universal sizing, is increasingly being discussed on fashion blogs and at industry gatherings as a common-sense solution to America's crisis. But there's a very good reason it won't work. And to understand why, it helps to understand how sizing came to exist in the first place.

I'm at a boutique in Rome, surrounded by retro-chic clothes that would look right at home in Betty Draper's closet—bold patterns, colorful capes, high-waisted skirts. It feels oddly appropriate, given that I'm here to be measured for a custom dress, something most American women haven't done since the 1950s.

The designer is Tina Sondergaard, a Danish woman who opened her first store in Rome in 1988. Since then, she says, she has outfitted everyone from hotshot executives to Italian rock stars to a German princess who "drove by on her Vespa, left it in the middle of the street, walked into my shop and said, 'I need that dress.'" By comparison, an American journalist is probably not that exciting. But if Sondergaard is thinking that, it never shows.

As she takes my measurements, I'm struck by how many choices I have. Do I want to show off my arms or hide them? Do I want to emphasize my waist? My legs? "Back in time, this is what people used to do," Sondergaard tells me, explaining how sizing worked for most of human history. If women were wealthy, they had their clothes made. If they weren't, they made their own. Either way, garments adhered to the contours of their bodies better than anything off the rack ever could.

In America, those cultural norms started to shift during the Great Depression, when barely anyone could afford to buy food, let alone fabric. At the same time, industrial techniques were improving, making it cheaper for companies to mass-produce clothes. By the end of World War II, those factors—alongside the rise of advertising and mail-order catalogs—had sparked a consumer revolution, both at home and abroad. Made to measure was out. Off the rack was in.

And sizes arrived. In the early 1940s, the New Deal–born Works Projects Administration commissioned a study of the female body in the hopes of creating a standard labeling system. (Until then, sizes had been based exclusively on bust measurements.) The study took 59 distinct measurements of 15,000 women—everything from shoulder width to thigh girth. But the most consequential discovery by researchers Ruth O'Brien and William Shelton was psychological: women didn't want to share their measurements with shopping clerks. For a system to work, they concluded, the government would have to create an "arbitrary" metric, like shoe size, instead of "anthropometrical measurement[s]."

So it did. In 1958, the National Institute of Standards and Technology put forth a set of even numbers 8 through 38 to represent overall size and a set of letters (T, R, S) and symbols (+, —) to represent height and girth, respectively, based on O'Brien and Shelton's research. Brands were advised to make their clothes accordingly. In other words: America had research-backed, government-approved universal sizing—decades ago.

But by 1983, that standard had fallen by the wayside. And experts argue it would fail now too, for the same reason: there is no "standard" U.S. body type. Universal sizing works in China, for example, because "being plus-sized is so unusual, they don't even have a term for it," says Lynn Boorady, a professor at Buffalo State University who specializes in sizing. But America is home to women of many shapes and sizes. Enforcing a single set of metrics might make it easier for some of them to shop—like the thinner, white women on whom O'Brien and Shelton based all of their measurements. But "we're going to leave out more people than we include," Boorady says.

Then again, the majority of American women are being left out right now.

I'm in a fitting room at Brandy Melville in New York City, a few steps from a sign promising that "one size fits most." At this store, there are no sizes—just racks of sweatshirts, crop-tops and short-shorts whose aesthetic could be described as Coachella-meets-pajamas. Many of Brandy Melville's teen and tween fans love this approach, in part because they can all try on the same clothes.

For me, it's a mixed experience. I'm 5 ft. 9 in. and, though we've already established sizing is meaningless, the clothes in my closet are mostly sizes 4 or 6. But when I try on the stretchy shorts and skirts, the fit is so tight it feels like I'm wearing underwear. Immediately I understand why critics say this store fuels body-image issues.

Brandy Melville denies it's exclusionary. "Anyone can come in the store and find something," its visual manager, Sairlight Saller, told USA Today in 2014 (the retailer declined to comment for this article). "At other places, certain people can't find things at all." The first statement is patently false: no one store can fit every human body. But the second is spot-on. Some of Brandy Melville's looser tops did fit me, and they could fit women who are much curvier than I am. Most retailers largely disregard the latter demographic.

This is a confounding business policy. The majority of American women wear a size 14 or above, which is considered "plus size" or "curvy" in the fashion industry. And they're spending more than ever. In the 12-month period ending in February 2016, sales of plus-size apparel hit $20.4 billion, a 17% increase over that same period ending in February 2013, according to the market-research firm NPD Group.

And yet, the plus-size market is treated as an after-thought. Nearly all advertising campaigns feature thin models. Most designers refuse to make plus-sized clothing. Some retailers have even launched plus-size brands only to kill them several years later, as Limited parent L Brands did with Eloquii (which was sold and relaunched by private investors after an outcry from consumers).

For shoppers, the message is inescapable: if you're over a certain size, you don't belong. "It's like we've been taught we all should have third eyes, and if you don't have a third eye, what's wrong with you?" says McCarthy, the Emmy-winning actress who has been "every shape and size under the rainbow" and is currently a size 14. "If you tell people that long enough, in 30 years everyone's going to go, 'You see that one? She's only got two eyes.'" In stores, she adds, the plus-size sections are often relegated to obscure areas, like the corner or on a different floor, if they exist at all. "If I have a friend who is a size 6, we can't go shopping together. They literally segregate us. It feels like you're going to detention when you go up to the third floor."

McCarthy isn't the only shopper speaking out. Earlier this year, blogger Corissa Enneking, who calls herself a "happy fatty," wrote a viral open letter to Forever 21 after encountering a plus-size section she describes as shoved into a corner "with yellow lights, no mirrors, and zero accessories." "Your reckless disregard of fat people's feelings is shameful," she continued. (At the time, Forever 21 said this wasn't an "accurate representation" of its brand.) Even Beyoncé, now considered an icon in the fashion world, has been vocal about how hard it is for women with curves to find clothes. Designers "didn't really want to dress four black, country, curvy girls," she has said of her early years with the group Destiny's Child. "My mother was rejected from every showroom in New York."

Clothing companies say that it's hard for them to make and stock larger sizes because it requires more fabric, more patterns and more money. That's all technically true, says Fiona Dieffenbacher, who heads the fashion-design program at the Parsons School of Design. "But if you have the volume of a big brand, it's a no brainer. You're going to get the sales." The more complicated issue, argues SUNY Buffalo State's Boorady, is that most designers still equate "fashionable" with "skinny." "They don't want to think of their garments being worn by plus-size women," she says.

Slowly, those biases are breaking down. Victoria's Secret, for example, is attempting to rebrand itself to emphasize comfort and authenticity ("No padding is sexy," a recent ad declares) after one of its competitors, Aerie, generated considerable buzz—and sales—by using models with rolls, cellulite and tattoos. Nike is using a plus-size model to sell sports bras. H&M is expanding its plus-size collection. And designers are starting to embrace a broader array of body shapes. (Consider Christian Siriano's collection with Lane Bryant and McCarthy's line, Seven7, which offer extensive plus-size options.) This is how fashion is supposed to work, says Sondergaard, the Danish dressmaker. "Many designers say, This is the dress, let's try to fit people into this. But it's the opposite: You look at people, and say, Let's try to fit a dress for this body."

Even as sizing becomes more inclusive, however, confusion persists: "size 20" is just as meaningless as "size 6." And for now, at least, the solution isn't design. It's data.

I'm in my apartment in New York, about to open a box that I'm told represents the future of retail. It's come courtesy of Le Tote, the startup I visited in San Francisco. Here's how the service works: I spend a few minutes awkwardly taking my own measurements with a measuring tape. Then I send that information to Le Tote, which runs my actual size—not the arbitrary numerical one—through its massive database of clothing measurements. Days later, I get a box of outfits picked specifically for my body.

The algorithm behind it all is called Chloe, and it's more encyclopedic than any human salesclerk. In addition to tracking my shape, Chloe can track my likes and dislikes. If I get a pair of boyfriend jeans that hang too loose, for example, I can tell Chloe I don't like that style, even though it technically fits. Next time Chloe will know to size down.

Online retailers are salivating over technology like this, which may well enable them to win more customers. True Fit, a Boston-based startup with its own database of measurements, works with more than 10,000 brands, including Nordstrom, Adidas and Kate Spade. Its algorithm asks shoppers to enter the size and brand of their best-fitting shoe, shirt, dress, etc.; then it recommends products accordingly.

These services aren't perfect. Le Tote, for instance, doesn't yet offer petite and plus-size options, nor do many of the brands that work with True Fit. And it's hard to predict personal style. As True Fit co-founder Romney Evans puts it, "You can have someone who technically fits into a horizontally striped jumpsuit but hates Beetlejuice." To its credit, though, Chloe found clothes that worked well for my body. When I opened the Le Tote box, almost everything fit.

So, are we close to solving the sizing crisis? Yes and no. Startups like True Fit and Le Tote are certainly taking steps in the right direction, cutting through the chaos of Internet shopping to offer clear, actionable intel. Ditto brands like Aerie and designers like McCarthy, who are proving that it's good business to push the boundaries of traditional sizing.

There are many other entities trying to start a retail revolution. Among them: Body Labs, which creates 3-D fit models of the human body; Amazon, which recently patented a True Fit-like algorithm; Gwynnie Bee, which offers a clothing subscription service for plus-size women; and Fame & Partners, which allows shoppers to design their own dresses. It's too early to tell which ones will succeed.

But even if all of them flourish and sizing becomes radically inclusive and transparent, there's no guarantee that we—the shoppers—will like what we see in the mirror. Vanity sizing works because, deep down, we're all a little vain. And no matter how many strides it makes, the fashion industry can't change its raison d'être: to make us feel like better versions of ourselves, one outfit at a time. Sometimes, that requires deception. Often, it drives us crazy. That's why I hate fitting rooms—until I find something I love. •

Graphic sources: Lynn Boorady, SUNY Buffalo State; ASTM International; Getty Images; People magazine; NPR

Photos: Twiggy, Kaling: Getty Images; Collins: AP; Winfrey: Dave Allocca—DMI/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Correction: The original version of this story mischaracterized the number of partners/collaborators of the startup True Fit. As of August, the company works with more than 10,000 brands.

Source: https://time.com/how-to-fix-vanity-sizing/

0 Response to "If I Wear a Large Shirt What Dress Size"

Post a Comment